Last week, openSUSE Leap 16.0 was released. I didn’t give it the attention it deserved, in part because I’m also working on another project, that I want to share today: there will be no “Linux Kamarada 16.0”. Instead, Linux Kamarada is moving its base from openSUSE Leap to Manjaro.

](/files/2025/10/manjaro-kamarada.png)

Based on the wallpaper by PharaohSD/DeviantArt

Manjaro is a Linux distribution based on Arch Linux, which is known for its rolling release (continuous updates), minimalistic, and flexible design. However, Manjaro is designed to be easier to use and more stable than pure Arch Linux, making it more accessible to a wider audience, ideal for those who want the power of Arch without the complexity of configuring it from scratch. Developed in Austria, France, and Germany, Manjaro is suitable for both newcomers as well as experienced Linux users.

Just as openSUSE Leap provides binary packages in the rpm format, both Manjaro and Arch Linux provide binary packages in the pkg.tar.zst format. In addition to their official binary package repositories, they also have the Arch User Repository (AUR), a community repository of build scripts called PKGBUILDs. Instead of providing ready-to-use binary packages, the AUR provides instructions that the system follows to build and install packages locally. You can install everything from the most popular to the most unlikely programs from the AUR.

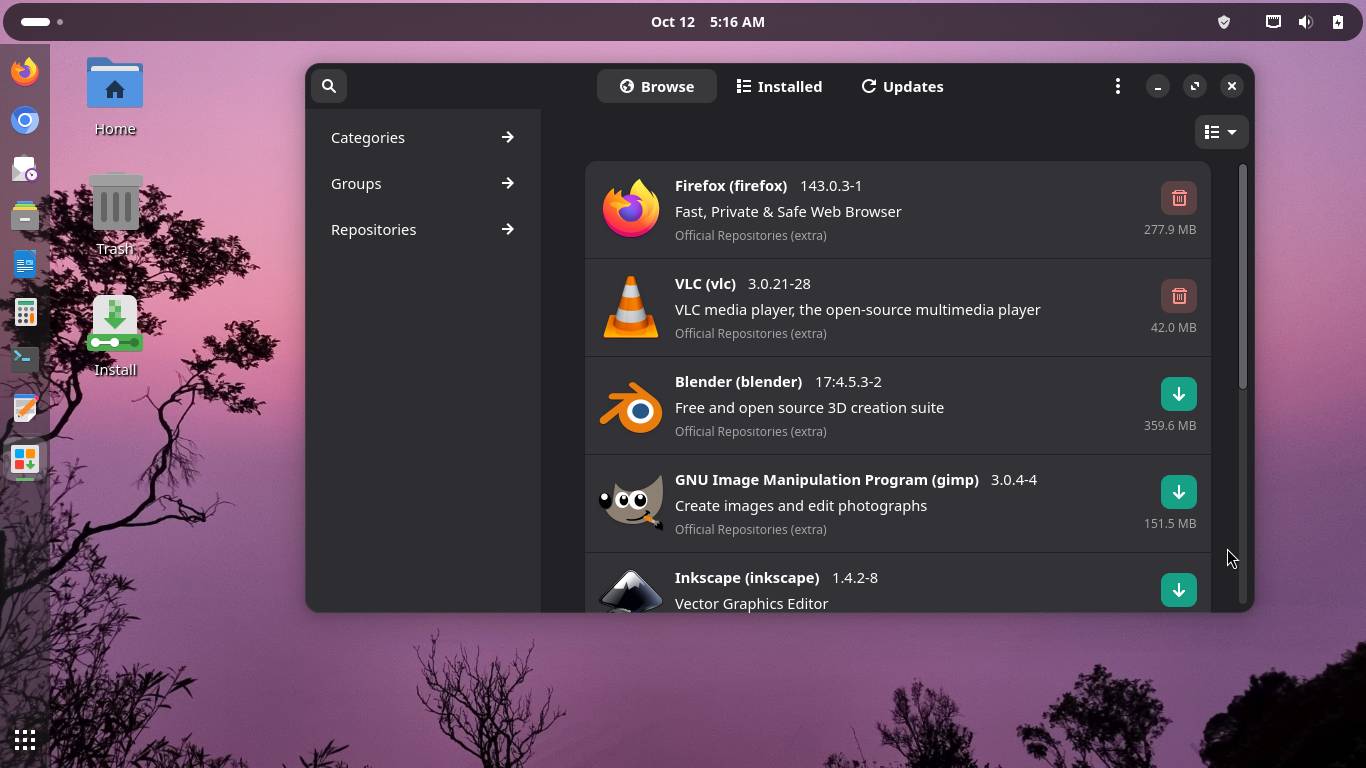

Software can be installed on Manjaro using Pamac, Manjaro’s own package manager, which has both graphical and command line interfaces, and can retrieve packages from the official repositories, but also from the AUR and Flatpak.

One of Manjaro’s distinguishing features is its Manjaro Hardware Detection (MHWD), which is especially useful for those who need to manage hybrid graphics cards on newer desktops and laptops.

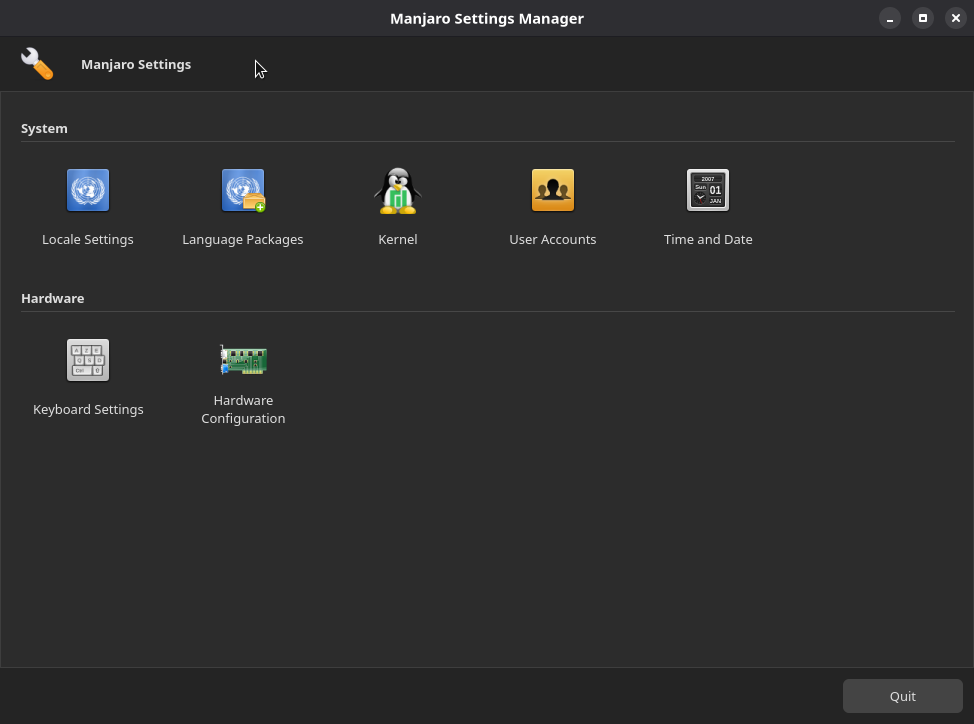

Manjaro Settings Manager (analogous to YaST) allows you to adjust various system-wide settings, such as language, kernels and drivers, user accounts, date and time, and keyboard layout.

How I met Manjaro

I started using openSUSE in April 2012. Back then, there was no distinction between Leap and Tumbleweed (nor the many other openSUSE flavors that exist today); it was just “openSUSE.” To test the distribution upgrade, I installed version 11.4 and then immediately upgraded to 12.1 (upgrading from one version to another was something I couldn’t do with the distribution I used before, Ubuntu. This is easy on Debian, which I also used for a while, especially when working with servers).

The colleague who introduced me to openSUSE soon switched to Arch Linux, but I didn’t feel like trying it. From what he told me at the time, it seemed a bit “Spartan”. But every now and then, googling how to solve a Linux problem, I’d come across the Arch wiki, a valuable source of information. Half a dozen articles on this site cite the Arch wiki, the most recent of which, from March, is about WSL.

Years later, another colleague spoke highly of Manjaro, but it wasn’t my turn to try it yet. I first met Manjaro while experimenting with the Raspberry Pi and PinePhone. Manjaro was one of the first Linux distributions to fully support both devices, surpassing openSUSE Tumbleweed.

As time passed by, I gradually became annoyed with some aspects of openSUSE Leap. For instance, this website is built with Jekyll, which depends on Ruby and other libraries. From openSUSE Leap 15.5 to 15.6, Ruby was not updated. But Jekyll and its dependencies are constantly updated. At one point, I couldn’t keep up with these updates because of the obsolete Ruby version, and I had to stick with that version of Jekyll. Updating Ruby wasn’t an option because of YaST, an essential system tool that also depended on Ruby.

When using regular releases distros, like openSUSE Leap and Debian, at some point you start having to tweak your system configuration and worry about which version of which software works with which version of other software – a hassle you wouldn’t have if you simply used the latest version of everything. There comes a time when you can no longer update the tools you need because your operating system’s core does not allow it. And then their very concept of “stability” becomes questionable. Because for those distros, “stable software” often mean “old software”, but newer versions also bring security fixes and performance improvements.

I don’t like that feeling of “fighting the computer”, I like things that “just work.” openSUSE used to be like that, but it’s not anymore. I could have tried openSUSE Tumbleweed, but remembering my experiences with the Raspberry Pi and PinePhone, I decided to give Manjaro a try.

And I liked it; it was a no return path. I installed Manjaro on my previous laptop, an Acer Aspire E15, initially besides openSUSE Leap. As that didn’t work, I ended up removing openSUSE and leaving only Manjaro. I had Bluetooth issues too, but I had the same issues when I installed openSUSE on that laptop, so I blame the computer, not the distros. That was August last year.

In November, almost a year ago, I changed my laptop. Today I have an Acer Predator Helios Neo 16, which has a hybrid Intel and NVIDIA graphics card, and configuring the graphics card was made much easier by Manjaro Settings Manager. This new laptop didn’t know openSUSE; just Manjaro.

openSUSE Leap versus Manjaro

Summarizing the differences between openSUSE Leap and Manjaro that caught my attention the most and made me migrate from the first to the second:

-

Software repositories: in addition to the official repositories, and Flatpak, which is supported by both distributions, Manjaro has the AUR and openSUSE Leap has the OBS. However, it is much easier to find packages in the official Manjaro repos and in the AUR than in the official openSUSE Leap repos and in the OBS. Therefore, in Manjaro, most programs can be installed in a way that’s more natural to the system, and Flatpak is a last resort. The variety of software available in the AUR is truly impressive.

-

Newer software: this is due to the different nature of the two distros – openSUSE Leap releases regular versions (usually one new version per year), while Manjaro is a rolling release, meaning there are no different versions of Manjaro, but just the latest version. In this aspect, Manjaro is similar to openSUSE Tumbleweed, which is also rolling release. For those like me who come from a history of regular release distros (Debian, Ubuntu, openSUSE Leap), the idea of using a rolling release distro may seem daunting at first, but these distros are now mature enough so that the frequent updates don’t usually break the system.

-

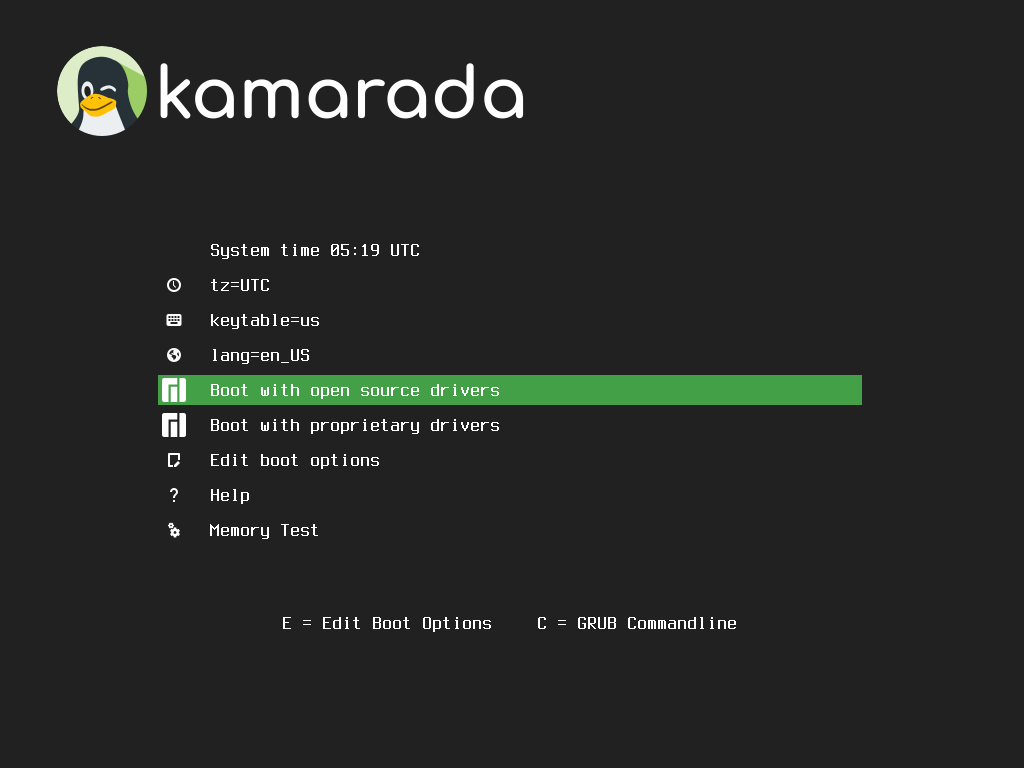

Live images: in my opinion, live images are one of the main features that distinguish Linux from other operating systems such as Windows and macOS. They allow you to use Linux without having to install it on your computer. This can be useful for those who want to test the system and/or learn how to use it before installing it, or for troubleshooting issues with the installed system when it is not able to boot, among other use cases. In this sense, Manjaro is more similar to other distributions like Ubuntu: they have always offered live images for download on their official websites. In the case of openSUSE, this has always been a back-and-forth: until openSUSE 13.2, live images could be downloaded from the distro’s official website. With the launch of openSUSE Leap, they stopped making live images (that’s when I started Linux Kamarada, to fill that gap). Then, they went back to making live images and making them available for download on the website. With Leap 15.6, the links to the live images were removed from the website, but they could still be found on OBS. Now, with Leap 16.0, they’ve apparently stopped making them again. Linux Kamarada has always been more similar to Manjaro, Ubuntu, and other Linux distributions at this point.

-

Hardware support: as already demonstrated with the Raspberry Pi and PinePhone examples, Manjaro appears to take less time than openSUSE to offer support to new devices. Desktops and laptops with NVIDIA graphics cards are another example: Manjaro has included NVIDIA’s proprietary drivers in its ISO images since at least 2019, simplifying and improving the experience for their users from the very first contact with the system. Even before that, since at least 2013, installing those drivers has been facilitated by MHWD. In openSUSE, installing these drivers has always been a manual procedure.

-

Bigger community: I have the impression, from what I see on news websites, forums and groups, that Manjaro has received more attention than openSUSE Leap. (This is just my impression; I don’t have statistics to support this perception.)

-

Git-only development: here’s a more technical breakdown of how things work behind the scenes. openSUSE development takes place primarily on OBS, while it is possible to integrate it with GitLab (or GitHub, or other Git hosts). Manjaro development, on the other hand, takes place primarily on Git. The Manjaro ISO image is built using GitHub Actions. The AUR is a Git host, with each “package” having its own Git repository. I understand that when OBS was created, there was no such thing as GitHub Actions, and in that respect it has its merits. But using Git to manage source code and GitHub Actions to build it makes development much more fluid. Even openSUSE is migrating from OBS to Git, but it’s “late to the party”.

Of course, this is just my humble opinion, based on my own experience using both Linux distros. Don’t take this comparison as a verdict or a scientific fact. You may disagree and think that openSUSE Leap is better than Manjaro, and that’s fine.

Goodbye, openSUSE

So, I used openSUSE for 12 years, from April 2012 to August 2024. I allowed myself to use and test Manjaro for a year to make sure it was what I wanted. I released another openSUSE Leap based version of Linux Kamarada, even though I was using Manjaro already, to say goodbye to openSUSE Leap with a current and supported version. With the openSUSE Leap 16.0 release, this is no longer the current version, so I think it’s fair to announce that there will be no “Linux Kamarada 16.0”. Since openSUSE has decided to make major changes in the new Leap release (for example, discontinuing YaST), I thought it would be an opportune time to also make major changes to Linux Kamarada. Following the same philosophy that led me to create Linux Kamarada – to show people “Linux as I see it” – since now I use and recommend Manjaro, from now on Linux Kamarada will be based on Manjaro.

I thank the openSUSE Project for all the good things it has given me over those years, especially the excellent distribution, and the infrastructure and knowledge I needed to build my own Linux distro. But now I’ve decided to go in a different direction.

Manjaro: the future of Linux Kamarada

From now on, articles on the website will use Manjaro as the reference Linux distribution. I may occasionally talk about openSUSE, but that won’t be the focus.

I plan to release a Manjaro-based version of Linux Kamarada by the end of the year. For now, I’ve updated the Download page with an ISO image that you can download and test to get a preview of what you’ll find in the final release. This version is not ready for daily use yet; it’s still in development phase, at a very early stage, I would call it alpha.

openSUSE Leap 15.6 will receive updates and support until April 2026. Therefore, Linux Kamarada 15.6, which is based on openSUSE Leap 15.6, will receive updates and support for the same period. Until then, Linux Kamarada 15.6 users will have to choose one of two possible paths:

- stay on the openSUSE Leap base, and upgrade from Linux Kamarada 15.6 to openSUSE Leap 16.0; or

- if you want to continue following Linux Kamarada, which will change the base to Manjaro (incompatible with openSUSE Leap), you will need to format your Linux Kamarada 15.6 partition to install the new Manjaro-based Linux Kamarada when its final version is released.

Please note that Linux Kamarada 15.6 is free (libre) software and its source code is available on GitLab and on the openSUSE Build Service. There’s a tutorial on how to build the ISO image yourself on your own computer, as well as a whole series of tutorials on how to build an openSUSE-based Linux distribution. Anyone who wants to fork Linux Kamarada 15.6, upgrade it to openSUSE Leap 16.0, and continue working on it, is welcome. Of course, I ask to change the name and the artwork.

The Linux Kamarada infrastructure is also going to change. I’m migrating the Git repositories back to GitHub. Even though I personally prefer GitLab’s interface, this is a market decision: GitHub has more users than GitLab (150 million versus 50 million, respectively, according to estimates from both) and this should give the project more visibility and facilitate potential contributions. Of course, if self-hosting is ever considered concretely, GitLab would be a good option.

Packages for the new Manjaro-based Linux Kamarada are currently hosted at kamarada.github.io/repo, but I plan to move them to somewhere like repo.linuxkamarada.com. When that happens, I’ll let you know.

You can get the source code for any package typically by accessing the GitHub repository with the same name as the package. For example, the source code for the kamarada-gnome-settings package can be found in the kamarada-gnome-settings repo on the Linux Kamarada GitHub.

That’s all for now. And what great news! To stay up-to-date on upcoming Linux Kamarada news, follow the project on social media. See you next time!

Specs

To allow comparing Linux Kamarada snapshots, here is a summary of the software contained on Linux Kamarada 25.10 Alpha:

- Linux kernel 6.16.8

- X.Org display server 21.1.18 (with Wayland 1.24.0 enabled by default)

- GNOME desktop 48.5 including its core apps, such as Files (previously Nautilus), Calculator, Terminal, Text editor (gedit) and others

- LibreOffice office suite 25.2.6

- Mozilla Firefox 143.0.3 (default web browser)

- Chromium 141 web browser (alternative web browser)

- VLC media player 3.0.21

- Evolution email client 3.56.2

- Brasero 3.12.3

- CUPS 2.4.14

- Drawing 1.0.2

- GParted 1.7.0

- HPLIP 3.25.6

- Java (OpenJDK) 21.0.8

- KeePassXC 2.7.10

- PDFsam Basic 5.3.2

- Pidgin 2.14.14

- Python 3.13.7

- Samba 4.23.0

- Tor 0.4.8.18

- Transmission 4.0.6

- Vim 9.1.1734

- Wine 10.15

- Calamares installer 3.4.0

- Flatpak 1.16.1

- games: AisleRiot (Solitaire), Chess, Mahjongg, Mines (Minesweeper), Nibbles (Snake), Quadrapassel (Tetris), Reversi, Sudoku

That list is not exhaustive, but it gives a notion of what can be found in the distribution. Please note that Linux Kamarada is now a rolling release distribution, meaning there are no different versions of Linux Kamarada, only the latest version. The number “25.10” does not indicate a version; it’s just a reference, and means “October 2025”.